We all need to hide our scars. On June 01st 1954 history of a sort was made. In the Peanuts strip (above) of that day we see a tiny Linus holding tightly to a blanket. Charlie Brown asks Lucy why Linus holds his blanket like that. Replying, Lucy isn’t sure but says that maybe it gives him a sense of security. And so the concept of the ‘security blanket’ came into popular consciousness. Though Charles Schulz brought the security blanket into public view he didn’t invent it. ‘Security’ blankets were used (probably in the wealthier households) to stop a baby from being restless or moving during the night in the 1920s by essentially securing the infant to the bed. The object wasn’t cruelty but to keep the baby warm in often cold houses. During World War Two the US military adopted the term ‘security blanket’ as a metaphor for keeping particular information secret and it’s still common for it to be used in this context. Schulz himself never claimed to have originated the security blanket. The Oxford English Dictionary Editor, John Simpson wondered about the origins of the phrase and wrote to Schulz. In a November 6, 1981 reply, Schulz doubts that he ever used the term, and he suggests that his readers may have coined it:

In the Peanuts strip, Linus held a blanket and he and the others discussed the security of holding the blanket, but I think that it was the readers who eventually coined the phrase “security blanket.” It is, therefore, impossible for me to date the origin of the term.

It’s very possible that people adopted the phrase influenced by Linus and his blanket and there’s no doubt that a kid’s blanket has now the ‘security blanket’ moniker. In a 1956 strip the blanket is called ‘a security and happiness blanket’ so the term was definitely in the air.

The question is why a little kid would need a security blanket? Later, Schulz would claim Linus as the ‘house intellectual’ who was the most well-informed which conversely led to a heightened sense of insecurity. In introducing Linus to the blanket Schulz also introduced him to the concept of dependency. Studies have shown that almost 70% of children develop strong attachments to objects such as teddy bears or blankets. These children give their blanket or teddy bear a special status and special attributes and will often refuse to swap it for something else or even a newer version of the same toy. People, even at a very young age, seem to have a tendency to anthropomorphise objects and give the inanimate a ‘life’ that echoes or betters their own. They know the objects aren’t ‘alive’ but give them a life anyway. We play God very early. We need objects to believe in and we need those objects (or more accurately ‘subjects’) to believe in us. A refusal to let go of the familiar and the known also could be at the bottom of the security object issue. It is something that stays with us and eventually transforms into a ‘better-the-Devil-you-know’ conservativism or a refusal to move forward. Interestingly some Eastern beliefs consider that every object has a lifeforce so if we want to be slightly mystical we could say that perhaps young children can sense this where we adults cannot.

Lucy’s baby brother was first mentioned on July 14th, 1952 and Linus first appeared on September 19th of that year as a baby too young to sit up by himself. We don’t discover his name until three days later.

So why would Linus need a security blanket? Well, the first time we discover that Lucy has a baby brother at home is when she’s trying to swap him for Charlie Brown’s tricycle claiming that Linus is no good to her. It doesn’t bode well for him. The first proper word (so to speak) we hear Linus say is a ‘Ha!’ of disgust when Lucy lies to her mother (in the early strips we occasionally heard adult parent voices) about being nice to her brother. His only previous sound was to snarl at Charlie Brown who was trying to take a ball from him. To put it bluntly Linus’s first word is one of anger and disappointment which echoes Schulz’ s claim that Peanuts is an ‘exercise in disappointment’. This is a remarkable statement in the context of the USA of the time and also our contemporary times in which literature considered for children (though Schulz never considered that Peanuts was for children) is very often geared to a somewhat grating positivity:

‘Charlie Brown was born to lose. He would never get to kick the ball Lucy Van Pelt held for him, just as he would never pluck up the courage to talk to that Little Red-Haired Girl, just as black-haired, black-hearted Lucy herself would never win Schroeder away from eternal, fanatical practice on his toy piano.’

Or/And

‘Schroeder’s friends will never understand Beethoven. No one will want to listen to Woodstock’s long winded stories. Peppermint Patty will never be appreciated as the great caddy she knows she is and her gal Friday, Marcie, will probably never stop being disappointed in, well, Peppermint Pattie. “Always an embarrassment, sir.”’

Even Snoopy, Charlie Brown’s dog, the epitome of the canine narcissist, knows in his heart that he’s not a World War One Flying Ace or a Legionnaire but just a dog depending on others not to starve. Worse, he knows if somehow, he managed to realise his dreams, he would actually make a terrible pilot. Even in his fantasies he always loses to the Red Baron, he always gets lost in the desert trying to find Fort Zinderneuf.

In a March 1953 strip, we see maybe the origins of Linus’s need for some sense of security when the predictably thoughtless Lucy shatters his nerves by shouting at him. In June 1953 we see him ‘think’ for the first time and once again it’s an episode of disappointment as Lucy isn’t aware of or ignores Linus’s great achievement of putting one block on top of another. His first proper conversation (albeit with himself) is in January 1954 when he complains about ‘big kids’ and inevitably the big kids come and take all the toys away. It’s no wonder kids cry often.

Some Peanuts strips are funny. Most aren’t. What’s funny about Sally telling Linus ‘if I hold my hands out like this, you can put a Valentine right in them’ and Linus replying ‘Or you can stand there for the rest of your life and never get anything’? Disappointment and casual cruelty are the lot of the majority of Peanuts characters to some degree or other:

Every day they have a list of great expectations of how their day will go, and by age five they are already learning that life is mostly not going to go as planned. Lucy will “probably never get married” and as much as Peppermint Patty studies she will somehow always know less than before. I think Schulz could have written a great self help book titled, “How To Be Disappointed.” In fact if he were coming up today, literary agents would probably be forcing him to do so. (Ibid)

It’s not that the conversation is funny (apart from in a very dark way). It’s more the fact that deep in our hearts we know that despite all the promises of the advertising around us promising the world and all the politicians/philosophers/academics telling us we can be whatever we want to be we’re going to have to ‘settle’ for perhaps a vague but persistent sense of disappointment or forever be Sally Brown holding her hand out waiting for a Valentine that will never arrive.

Of course, Peanuts is Schulz and Schulz is Peanuts. Literally. Almost nobody else in five decades penned it. Every character, every word, was drawn and written by Schulz (apart from a series of disappointing comic pieces that Schulz (unwisely perhaps) farmed out to other artists at the height of Peanuts-mania when he literally couldn’t meet demand for new strips) and therefore we can see that the two major disappointments in Schulz’s life were articulated in the strips. Schulz’s mother died as he was sent to the War arena in the 1940s. He was heartbroken, particularly as he never got to say goodbye. Likewise, he never got over his marriage proposal being turned down by Donna Mae Johnson, the inspiration of the Little Red-Haired Girl. These were the two catalysts the drove a lot of the disappointment and cruelty within the strips. He hated the title ‘Peanuts’ also and perhaps a part of him consciously or unconsciously fought against the cutesy title.

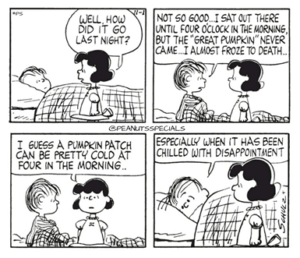

Linus of course has his own fair share of disappointment. Every Halloween he patiently waits in vain for the Great Pumpkin to appear in his pumpkin patch. Not only that he is an evangelist for the Great Pumpkin and never loses a chance to attempt to convert anyone he meets. Inevitably he is met with much mockery and ridicule. Schulz was religious but not the hellfire and brimstone type and eventually he would say he was a ‘secular humanist’:

“I do not go to church anymore, because I could not be an active part of things. I guess you might say I’ve come around to secular humanism, an obligation I believe all humans have to others and the world we live in.”

Linus waiting eternally For the Great Pumpkin to appear could be seen as a comment on the value/hopelessness of faith. Perhaps Schulz was aware of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot which first appeared in the early 1950s and adapted it into the Peanuts World. Indeed, there are striking similarities in the minimalist staging of Beckett and the sparse use of space by Schulz in his cartoon strips.

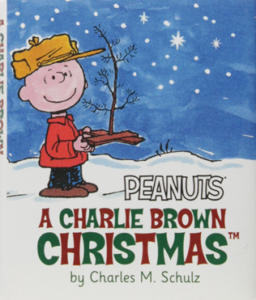

There are even echoes of Giacometti’s tree in A Charlie Brown Christmas:

“VLADIMIR: (after a moment of bewilderment). We’ll see when the time comes. (Pause.) I was saying that things have changed here since yesterday.

ESTRAGON: Everything oozes.

VLADIMIR: Look at the tree.

ESTRAGON: It’s never the same pus from one second to the next.

VLADIMIR: The tree, look at the tree. Estragon looks at the tree.

ESTRAGON: Was it not there yesterday?

VLADIMIR: Yes of course it was there. Do you not remember? We nearly hanged ourselves from it. But you wouldn’t. Do you not remember?

ESTRAGON: You dreamt it.

VLADIMIR: Is it possible you’ve forgotten already?

ESTRAGON: That’s the way I am. Either I forget immediately or I never forget.”

The trees in Godot and A Charlie Brown Christmas offer an alternative to the prevailing conditions; the eternal wait in the former and the overwhelming commerciality of Christmas in the latter. The tree in Godot could assist in ending the characters’ lives and agony and Schulz’s tree offers Charlie Brown a path to a better understanding of Christmas. Both trees, if recognised as such are a conduit to perhaps a better place, even a redemption. Both trees also echo Christ’s cross and crucifixion.

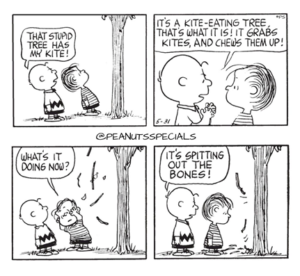

You could imagine Charlie Browne saying ‘Either I forget immediately or I never forget’ particular in relation to his nemesis, the kite-eating tree. The kite eating tree first appeared in April 1956 but wasn’t named until March 1965. Charlie Brown loses his kite continually to the tree. Other kids, quite understandably fly their kites elsewhere but Charlie Browne seems to have a particularly strange, slightly masochistic relationship with the tree as it eats kite after kite. Eventually Charlie Brown in frustration would bite the tree and run away when he discovers that it is illegal to bite trees and ends up sleeping not in a bin but in a carboard box.

You can also imagine Lucy appearing in a Beckett scenario, delivering ‘wisdom’ from her psychiatrist’s booth. The never-ending losing streak of Charlie Brown on the baseball mound is pure Beckett. The baseball mound in Peanuts year upon year reinforces defeat (and yet never giving up) for Charlie Brown. Every year might be ‘this year’ for Charlie Browne just as Winnie in Happy Days assures us ‘This will be a happy day’. But ‘sorrow keeps breaking in’ for both. Or Linus and Charlie Brown at their wall discussing the whys and wherefores of existence. Both Beckett and Schulz could be equally moving and bleak.

The kite eating tree is a sign of Charlie Brown’s ineffectiveness. Objects in Peanuts often are. It could be said that Linus’s security blanket was another sign of ineffectiveness articulating his inability to deal with what the world throws at him. Though encouragingly Linus has made the best of things and can wield the blanket like a whip and fold it into various shapes. Schulz on occasion anthropomorphises objects, the school building, the kite eating tree, the baseball mound and even Linus’s blanket when he made it growl and snarl at Lucy.

There are a series of strips in the early 1960s that mimic the cold turkey of drug dependency as Linus’s Blanket Hating Grandmother (her official title/name) and Lucy try to cure his addiction to it. In the strip he is literally shaking with withdrawal and anger. Schulz didn’t try to hide that the other side of a need for security is that the need can easily become a dependency. Rerun, Linus’s brother recognised this when in looking for a role model he wonders if the neighbour’s dog (Snoopy) is allowed to be a role model for him. He explains that theoretically an older brother should be a role model but ‘the blanket business takes care of that:

In the end, Linus and all the characters in the Peanuts world are caught in a Beckettian world of never-ending insecurity, unrequitedness and ‘fail/fail better’. Though that phrase has recently become a mantra for the inspirational, it really has no positivity about it. Imagine, fail, then fail better. Forever. Think about that.

Next, Lucy.

Greg McCartney

Much appreciation goes to the Arts Council of Northern Ireland who made these series of essays possible through their Artist’s Emergency Fund.