It might seem strange to younger as they say viewers, but if you’re in your mid-fifties you were born twenty odd years after a World War, after a Holocaust, after an ‘Iron Curtain’ was drawn across Europe and after the first nuclear bombs were detonated over Japan. This has to have had an effect on the psyche. Add that to an Northern Irish ‘Troubles’ for those born here and it’s little wonder that we’re messed up.

In Britain, over 450,000 British soldiers and civilians had been killed and many more wounded physically and mentally. It was a struggle to adjust to the post war situation for many individuals and communities:

According to Lynn Abrams, women were torn between the traditional conservative discourse of ‘social duty’, linked to their roles as mothers and wives, and the opportunities for freedom, choice and self-fulfilment generated by more liberal approaches to women’s education and careers. As well as coping with memories of conflict, young men too struggled to adapt to shifting patterns of work and home life, to adjust to the changing conditions of industrial labour and to re-establish relationships with their families that had been disrupted by the war. First and second generation immigrants faced prejudice, hostility, violence and the difficulties of cultural assimilation.

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436946/)

You read a lot of comics that had the war as its background, saw a lot of tv programmes ranging from Dad’s Army to Colditz and watched a lot of (usually American) war films on a Sunday or at Christmas. What follows is a short survey of post-war British war comics, concentrating on the ones that I would buy regularly, Warlord, Battle and occasionally, the pocket war library series. It focuses on boys comics as those were the ones I read. At that time if you were caught by your friends reading girls’ comics it wouldn’t have gone too well, but I must admit I did have a liking for Misty and its supernatural tales in particular.

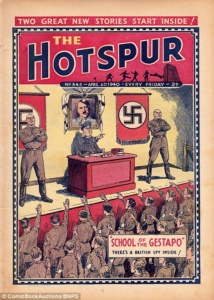

The major British comic publisher from the 1920s/1930s and beyond was D.C Thomson based in Dundee, Scotland, at that time and for many decades afterwards notoriously anti-union and known locally never to employ a Catholic. It’s ‘big five’ comics were Rover, Adventure, Wizard, Skipper, and Hotspur. These were very text-heavy publications featuring various adventure stories for boys. They were immensely popular, selling millions weekly.

Adventure was the first of the ‘Big Five’ with the first issue published September 17th 1921 and ran to 1878 issues. The boys’ story paper market at the time was dominated by titles such as Gem and Magnet with school stories about Billy Bunter and his other public school chums and many of the big five titles would also feature public school educated protagonists or were actually set in public schools such as The Red Circle in the Hotspur for instance.

During the War children’s comics, such as the Beano and Dandy (published by D.C Thomson in Dundee, Scotland (who were known locally to never employ a Catholic) character’s would take on Hitler’s armies in humorous and imaginative manners. In fact it’s been said that as well as the editors of national newspapers the Beano and Dandy editors were on an arrest list if the Nazis had invaded Britain. Adolf Hitler and his deputies such Hermann Göering, not to mention, Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini were lampooned in each comic. Copies of The Beano were even sent to soldiers serving overseas to boost morale, though whether they were effective is another thing at all. Readers were urged to follow wartime advise and aid the war effort by recycling paper for instance.

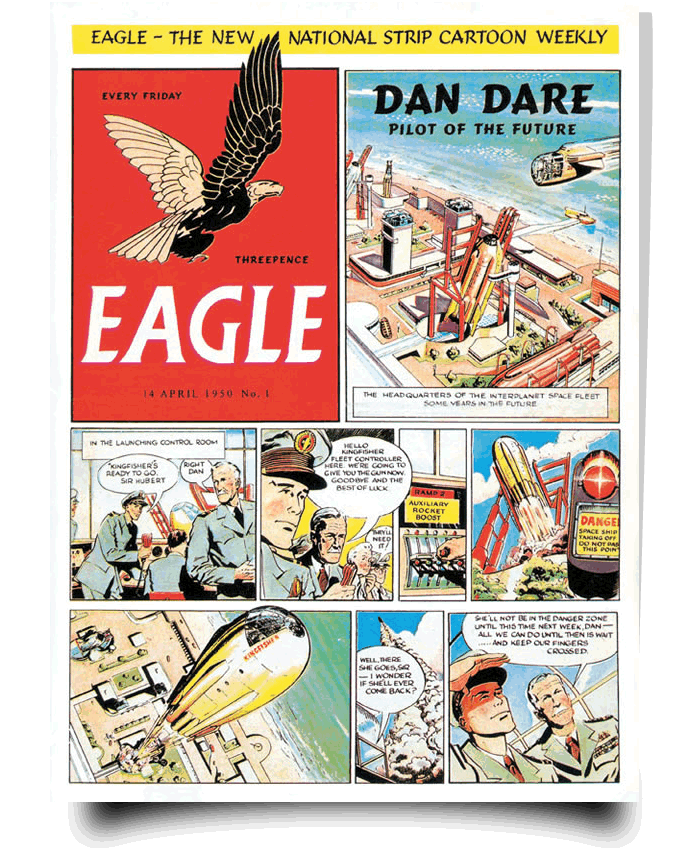

By the 1950s over ten million comics were being sold weekly and it has been estimated that a single comic issue would have 30,000 – 40,000 words, it was quite an investment in time for the young reader. Comics were relatively cheap and the working class children could avail themselves of them, with one comic being handed around numerous kids. D.C Thomson would be shook out of its somewhat complacent attitude to its products with the emergence of Eagle Magazine in 1950 which had, influenced by the American comic industry a focus on the visual. Eventually most of D.C’s output would abandon their text-based approach.

The Eagle was conceived of by an English vicar called Marcus Morris. He was disappointed by the state of British comics and appalled by what he considered as the horror and violence of American comics that were making their way into the UK at the time. He wished for something more uplifting and moral that would essentially teach children to be responsible citizens, writing to his local paper:

Many American comics were most skilfully and vividly drawn, but often their content was deplorable, nastily over-violent and obscene, often with undue emphasis on the supernatural and magical as a way of solving problems

He received a very positive response to this (presumably from parents rather than children who were presumably quite enjoying the supernatural and magical) and so set about creating a very moral and upstanding character called, without much subtlety, Lex Christian, though this name was rejected unsurprisingly as being too overtly evangelical. The original plan was also to create newspaper cartoon strips but Morris wasn’t very successful in this so the idea of creating a comic themselves was born. To create his new strip, he recruited fellow churchman Chad Varah who would go on to found the Samaritans in 1953 to write the stories and Frank Hampson to draw it. Coincidentally, Morris had discover Hampson in a Southport art school and discovered that he was actually one of his parishioners.

Lex Christian would turn into ‘Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future!’ named, though no doubt few were aware of it, after a hymn: Dare to be a Daniel. Morris’s persistence eventually paid off and he found a publisher, Hulton Press, willing to take a chance on it. The magazine, backed by a large publicity drive was a huge success, it’s first issue selling over 900,000 copies. Though the launch issue included stories featuring upstanding cowboys and policemen, Dan Dare would be the start of the comic. Dare was a steel jawed upstanding figure that young people could look up to, who behaved by a high code of ethics. It’s easy to laugh at this now but Morris also wanted foreigners in his comic to be more than the usual racist tropes and he wanted ethnic minorities to be portrayed. Though it has to be said that the Mekon (Dan Dare’s evil nemesis) has been described as a ‘rich composite of racial stereotypes’, in particular Asian racist tropes and that most of the good guys are white .

Dan Dare was the first major Sci-Fi comic strip and it would have advisors such as a young Arthur C. Clarke. The Eagle itself would offer art opportunities to the likes of David Hockney and Gerald Scarfe. Dare and is crew portray an imagined and utopian Englishness:

‘In the very first Dan Dare adventure, which began to be serialised weekly in the Christian boy’s comic Eagle in 1950, we’re introduced to the ”Inter Planet Space Fleet some years in the future.” It’s an odd organization, in that it’s clearly meant to be Earth’s “Space Fleet,” but it’s clearly really just the Royal Air Force in orbit and beyond. The Fleet’s HQ is in England, and the Fleet’s pilots are predominantly English. It’s a strip proud of and haunted by England’s finest hour. The end is constantly nearing, and great sacrifices by good chaps are constantly required. Wonderfully conceptualized and executed by Frank Hampson and his team, it’s a rip-snorting adventure tale of upper-class, southern-English space pilots and their working class sidekicks.’

http://sequart.org/magazine/2591/dan-dare-and-the-seductive-myths-of-englishness/

People of colour occasionally appear but essentially it’s the white saviour of the galaxy syndrome. Most of the people that appear are upper-class. There’s a thesis to be written on why the heroes of comics read mostly by the working and middle class have usually upper-class protagonists. Perhaps it’s a throw-back to the Victorian era when reading was confined to certain classes. Perhaps it’s the British diffidence to the landed gentry and the wealthy (where else would Jacob Rees Mogg (who isn’t even that genuine) be taken seriously?) that is still an integral part of British society. There isn’t any other reason Downton Abbey would be popular. We still see it on films and television. Hogwarts is essentially a private school for the wealthy.

The scars caused by WW2 is clear on the psyche of the Eagle. The Earth’s armies have all been abandoned after a series of disastrous wars but it is still a very structured society reaffirming old societal models:

Dan Dare’s Earth is really still England. England has less embraced the wider world than simply swallowed it. We see few people who aren’t white, English and upper-class. There are some charming exceptions, but those apart, this is an England that has somehow set the template for the globe, and done so seemingly without weapons. (Perhaps the British Empire really was an utterly benign force there.) It’s a world of stiff-upper lips and cheeky, stubborn other ranks, of a fair and decent order where everybody knows their place, and yet where each rank further up the hierarchy deserves its power and reward, and uses them for those lower down the scale. It’s an olde English paradise.

Ibid.

It’s not that surprising. By the standards of the time, the Eagle wasn’t overtly jingoistic and racist. It probably, if we are being charitable to them, just didn’t occur to them to make the crew multi-cultural. This of course isn’t a good thing, reflecting much of the entertainment industries of the time.

That is not to say that the Dan Dare stories ignored real events. Readers would have appreciated the first Dare story, which was a desperate off-planet search for food for a starving Earth. This was a time of rationing and shortages so it’s appeal would be plain. Hampson admitted that Dan Dare came at a time of great shortages after a long and exhausting war: “Everything was very bare, everything was utility, everything was right down to rock bottom. So the fantasy of it had a great appeal.”

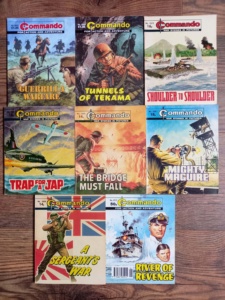

In 1958 War Picture Library was published by Amalgamated Press/Fleetway (now owned by IPC Magazines) and it’s original ran for over 2000 issues until 1984. It was a pocket-sized (A5-ish) publication, with each issue having just one story over its 64 pages. It was one of the first post war titles to set stories in WW2. Aimed at a young audience and written and drawn by people that had lived through the conflict themselves, sometimes actually being on the frontline itself, its remit was to show war it all its awful complexities rather than aim for pure heroic or jingoistic deeds. There would be a whole series of companion titles such as Combat Picture Library (1959) Commando (1961), Battle Picture Library (1961) and Battle Picture Weekly (1975). There would be over one hundred thousand of these produced between 1960 and 1992 and many titles are reprinted today although Commando is still soldiering on so to speak.

There was a realism to these titles that spoke of the personal experiences of many of their writers and artists. It’s not always easy to identify which writer did exactly what as they (along with artists) were mostly uncredited. As stated there was not that much jingoism in the content though given the context of the times there were definite racial stereotypes and quite a bit of ‘Gott in Himmel” and the like etc (the first and often only bits of German working class boys got to know) though there were at least attempts to make the enemy human with individual opinions and motivations. There were also tales of self-sacrifice and even critiques of those making decisions that would negatively affect men on the front line. Occasionally historical figures, such as Montgomery or Rommel would appear in them.

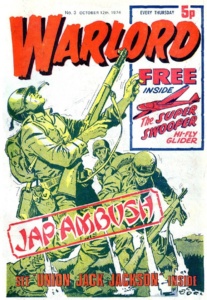

In 1974 DC Thomson launched Warlord, a war themed weekly comic. War is obviously very visual (mostly in unpleasant ways of course), something that Pete Clarke, Warlord’s first editor realised, so used full page spreads to start each story and cut down the number of panels on each page which allowed artists to platform their skills a bit more freely. The first issue of Warlord had six different strips of which four were set in WWII, and one in WWI plus a story set in British run India at some indeterminate time fore Indian independence. Characters in the early issues included the dodgy named Union Jack Jackson (a character rescued from the Hotspur text stories of times past), plus Spider Wells, Bomber Braddock and Lord Peter Flint. Features included True Life War Story and articles on weaponry called Weapons In Action. Most of the characters were the traditional square jawed type. Union Jack Jackson for instance was a Royal Marine who is separated from his service when the Japanese the ship he is stationed on. He is washed up on a Pacific island and is rescued by a platoon of US Marines, staying with them for the rest of the war. Flint was a James Bond type character. On occasion there would be sympathetic portrayals of Germans, usually someone from the Luftwaffe for example would be the ‘good guy’ in conflict with fundamentalist Nazis or in battle on the Eastern Front with the Russians. This avoided any accusations of being unpatriotic. One interesting thing at the time was what you could get away with cover wise despite the protestations of Mary Whitehouse and her ilk. The cover of Warlord issue three (below) for example has a US Marine getting killed in a Japanese ambush. Despite the crass lettering shouting JAPAMBUSH (which reads like something out of a Sun or Daily Mail headline) it’s a very arresting image.

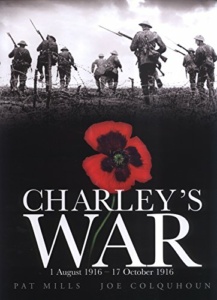

Warlord was very successful and soon after IPC responded with Battle Picture Library. Conceived by Pat Mills and John Wagner (later of 2000AD) it also was ever successful. Mills and Wagner wanted more working class representation in the war comic arena as traditionally war stories were fronted by middle or upper-class public school types with an occasional working class soldier as a plucky sidekick. We can see this in particular with regard to Charlie’s War, a strip written by Mills and drawn by Joe Colquhoun about WW1 that ran from 1979 until 1986. It has come to be regarded as a classic of the genre. Telling the story of a kid called Charley Bourne (Charlie Brown anyone?), who lies about his age and joins the British army even though he is two years too young. We see him develop from a brave if naive kid to a haunted adult.

The strip follows Charley into the trenches where the portrayal of war is very realistic, so much so that in some reprintings that followed some art was censored: As Pat Mills put it himself:

After all, when I wrote Charley’s War, I consciously set out to subversively attack the State for its war crimes in the Great War. Crimes which – as long as they remain unacknowledged – are a dark curse on our country’s national karma, poisoning the present and the future.

James F. Wurtz, Indiana State University writes:

‘Charley’s War was not simply thematically subversive, but its self-conscious use of the limitations and advantages of comic form allowed (and allows) it to stake a clear position against the capitalist and imperialist impulses of its historical context.’

The First World War was a war that should never have taken place. Millions were killed for the imperial ambitions of royal friends and cousins. And of course it paved the way for the horrors of the Nazis.

This has been a relatively quick survey of post-war British war comics and no doubt I have overlooked quite a few important things. It focuses on ‘Boys’ comics though there were frequent war stories in ‘Girls’ magazines. For example:

Between June and October 1960, Princess ran a story called “Nikola the Polish Refugee”. The heroine is a Polish girl, who loses her home and her parents when Germany invades in 1939 – all she has left is her doll. She meets an orphaned boy who is also homeless, and they become involved in fighting their way through the German occupation of Poland to reach the head of the Polish resistance with a message about a wounded pilot, hidden in her doll.

https://comicsuk.co.uk/forum/viewtopic.php?f=140&t=8191

Girls comics actually outsold boys on many occasions and here is a list taken from an online discussion of war themed stories in them:

The Kids of Camp Courage (Suzy) The Sentinels (Misty), Slaves of War Orphan Farm (Tammy), Catch the Cat! (Bunty), Detestable Della (Bunty), Somewhere Over the Rainbow (Jinty), Song of the Fir Tree (Jinty), Wendy at War (Debbie), The White Mouse (Emma), Come Home, Kathleen (Bunty), Mam’selle X (June and School Friend), My Name is Nobody (June), Dancing to Danger (Sandie), Vicky the Evacuee (Judy), The Silent Shadows (Sally).

(Ibid)

No doubt, as the titles indicate many of these stories were told in the context of what was expected from girls/women at the time but the fact that they are there at all shows that war stories were though appropriate for both sexes at the time.

War comics were published at a time still scarred by the Second World War, though perhaps unconsciously kids that read them in Northern Ireland (and children of both ‘persuasions’ did widely) could identify their preoccupations with war and death rather more immediately than English kids, as violence and death was on their streets on a daily basis. Comics or graphic novels as they are somewhat embarrassingly classed as these days were the gateway literature of the working class. Many of us who read these comics would make our ways into the local library and devour whatever kids books they held there, usually things like the Famous Five, ‘African Adventures’ the Hardy/Boys and Nancy Drew, Jennings as well as Tintin and Asterix. That many of these books contained many regressive social attitudes we honestly weren’t aware of, though for some reason I couldn’t ever bring myself to read Biggles. I honestly preferred the likes of 2000AD when it came along, even if its main character ‘Judge Dredd’, was a member of a totalitarian military police force. Maybe it’s because I never liked jingoism though ironically Dredd, who was never meant to be a hero, would become one for many readers who missed or ignored the point of the stories he featured in. Inevitably I couldn’t, given what went on in Derry fully identify with most of the army heroes portrayed in British comics so it was much easier to head to the future with 2000AD rather than concentrate on the past.

Many of the pocket sized war comics have been reprinted for a middle-aged audience hungry for nostalgia and a time when friends and enemies were more certain. The kids are busy blowing the heads of enemies on the Playstation and the Xbox in every war arena from WW2 to the far future. The hunger for war tales is still there but now they’re interactive and your character kills and gets killed. Time will tell if this is a good thing.

Thanks to The Arts Council of Northern Ireland for making this essay possible through support from their SIAP funding programme. It will also appear in the Honest Ulsterman.